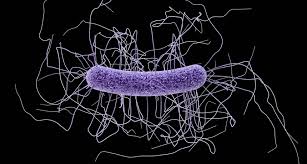

Clostridium difficile is a bacterium that is resistant to many antibiotics – hence the name “difficile” since it’s difficult to treat! It is the most common cause of infectious diarrhea in hospitals and nursing homes in Canada and other industrialized countries.

Most cases occur in patients taking certain antibiotics that kill a wide range of bacteria (referred to as broad-spectrum antibiotics) in high doses or for a long period of time. The normal bacterial flora in the digestive system that keep c. difficile in check is destroyed by the antibiotic, allowing the resistant c. difficile to take over. These infectious bacteria produce toxins that damage the bowel, and cause diarrhea and inflammation in the lining of the bowel.

Some people can have c. difficile in their bowel and not show symptoms, likely because other bacteria are keeping its growth in check. There are different strains of c. difficile and some cause more serious illness.

Stomach acid helps to kill unfriendly bacteria like c. difficile if we happen to swallow some. Acid-suppressing drugs, especially proton pump inhibitors (like Losec®, Tecta®, and Nexium®) that strongly block acid production, can increase the risk of a symptomatic infection of c. difficile.

How is it passed from person to person?

C. difficile bacteria and their spores are found in feces. People can get infected if they touch surfaces contaminated with feces and then touch their mouth… (How gross!) This helps you understand how important it is to wash your hands regularly!

If you are healthy, generally there is actually little risk of developing an infection. But in the elderly and those with other illnesses whose immune system may be less healthy, there is a greater chance of infection.

It’s important to keep the normal gut bacteria healthy. When there are fewer normal healthy bacteria in the gut, c. difficile have a better chance to grow and cause infection. Include fermented foods that contain live bacteria in your diet, and take probiotics after a course of antibiotics. This will help to replace the good bacteria that are often destroyed along with the bad ones that caused the infection and maintain a healthy gut flora.

What are the symptoms?

C. difficile infection causes watery diarrhea, fever, decreased appetite, nausea, and abdominal pain or tenderness. The diarrhea usually does not respond to regular diarrhea medications and will last more than the 2 or 3 days of diarrhea from other causes. A stool sample is often tested to confirm that the cause of the diarrhea is c. difficile.

How can you prevent c. difficile?

Wash your hands often with soap and water. Healthcare workers should always wash their hands after touching every patient to prevent passing bacteria and other infectious organisms from one patient to another (or to themselves!). At home, always wash your hands after caring for an ill person, using or helping with toileting and before preparing or eating food.

Alcohol-based hand washes help but are not as effective as soap and water as they do not kill c. difficile spores. Wearing disposable gloves when caring for someone with c. difficile is recommended and hands should be washed with soap and water when the gloves are removed.

How is c. difficile infection treated?

The antibiotic that caused the infection should be stopped right away, and a new antibiotic that kills c. difficile will often be started. Very mild cases may clear on their own.

C. difficile is resistant to many antibiotics, hence the name “difficile – difficult to treat! Metronidizole (Flagyl®) is an antibiotic that may be effective for mild to moderate infections. Vancomycin (Vancocin®) is used for more severe infections and it is considerably more expensive than metronidazole. A new antibiotic, fidaxomicin (Dificid®) showed better results against c. difficile in studies, but it is very expensive.

Taking probiotics (good bacteria in capsule form) in large doses has been reported to help when all else has failed, or as an add-on to antibiotic treatment. It also helps to prevent reinfection, which occurs in 20% of cases.

In extreme cases, the diseased part of the bowel may be surgically removed. Fecal microbiota transplantation (also known as stool transplant) is another new therapy that may be tried in recurrent infection. Donors are screened for infections, parasites, viruses and other bacteria. Stool from the donor is then placed into the infected person’s bowel using a colonoscope or nasogastric tube.

References

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/c-difficile/diagnosis-treatment/treatment/txc-20202426

Join my mailing list (see box in side bar or at the bottom) to receive a weekly email link to more health information… and to help me grow my blog! I really appreciate your support…