Researchers have learned that 18 commonly used classes of drugs can extensively affect the organisms that live in your gut. The most drastic changes were caused by stomach medications, antibiotics, metformin (a diabetes medication), and laxatives. Why is this important? Because research suggests that changes in gut organisms are associated with obesity, diabetes, liver diseases, cancer, degenerative nerve diseases like MS and ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) and others.

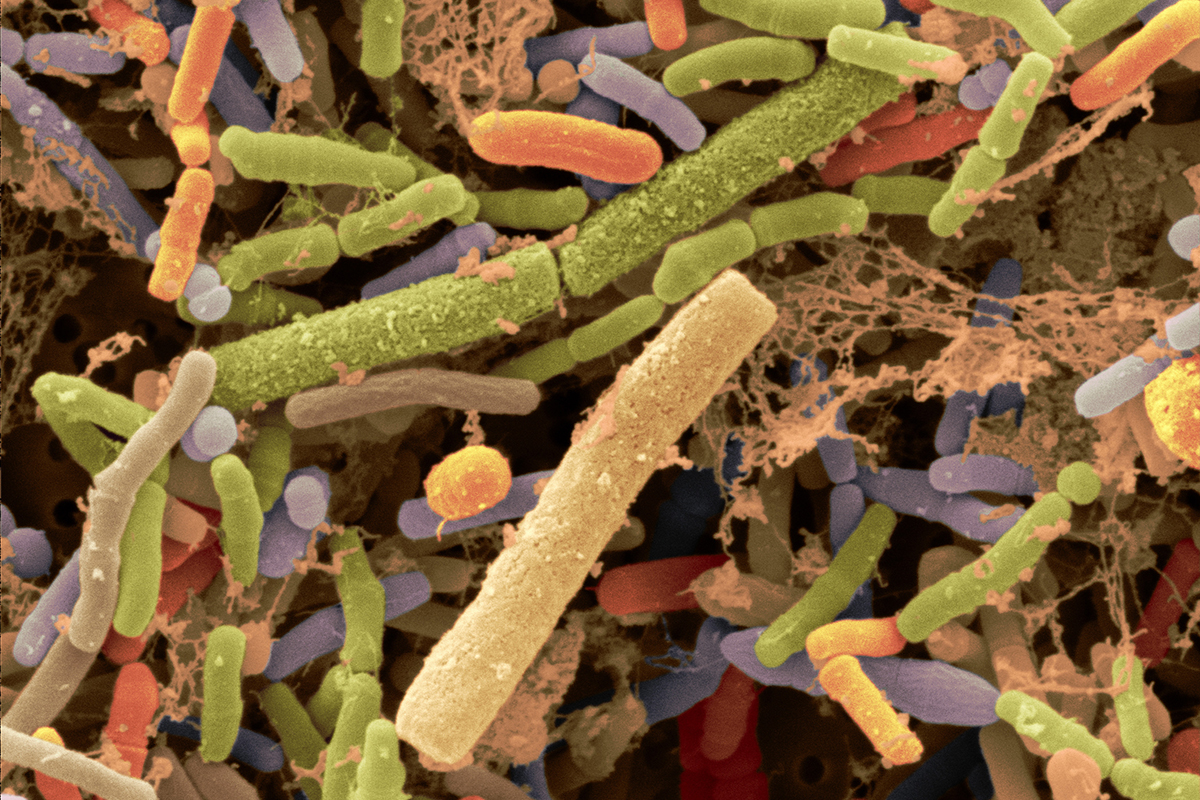

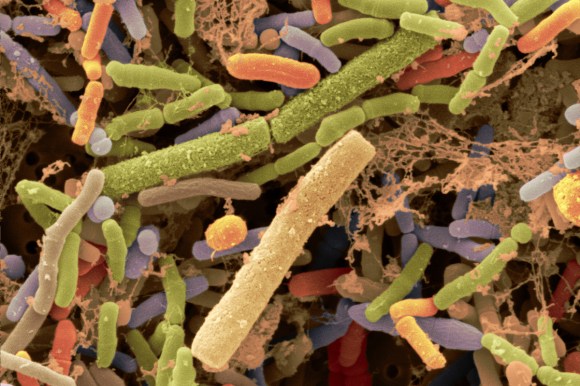

Your intestines contain tens of trillions of microorganisms, with at least 1000 different types of known bacteria. These organisms are vital for our health, breaking down food and toxins, making vitamins and training our immune systems. Their total weight is calculated to be as much as 2 kg (4.4 pounds) – heavier than the average brain! It’s also known as the human “microbiome”. It’s been increasingly studied over the past 15 years – what types or organisms are found in healthy people vs. those with various diseases, how we can improve the content and balance of organisms in our digestive systems and, now, how this microbiome is affected by common drugs.

New research, reported at the international United European Gastroenterology Week 2019 conference, describes work done at the University Medical Center Groningen and Maastricht University Medical Center in the Netherlands. Out of 41 drug classes they tested, 18 were associated with changes in gut microbiota composition or function. Several of these were found to be significant:

-

Antibiotics

-

PPI’s (“proton pump inhibitor” stomach medications)

-

Laxatives

-

Metformin

-

Oral steroids (i.e. taken by mouth)

-

SSRI antidepressants (in people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome)

Antibiotics kill bacteria both good and bad. Stomach medications, particularly PPI’s (proton pump inhibitors, like Losec/Prilosec, Nexxium, Tecta, Prevacid and others), drastically change the acidity of the stomach making a significant difference in the environment these organisms like to grow in. So, we shouldn’t be surprised that these 2 classes of drugs change which bacteria thrive in our digestive systems.

Laxatives speed the passage of the contents through the digestive system, pushing microbes out of their normal habitat as they move the entire contents of the intestines along more quickly than normal.

Another research team, at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Germany, suggests that altering gut organisms may also be part of how some drugs work. They noted that one of the ways the diabetes drug, metformin, works is to encourage the growth of certain bacteria. People who take metformin have also been found to have higher numbers of the potentially harmful bacteria, E. Coli.

The researchers also identified an increase in antibiotic resistance related to 8 different categories of medications, not just from use of antibiotics themselves. We always knew that oral steroids (those taken by mouth, like prednisone) cause people to gain weight, and now researchers in the Netherlands report that this may be caused by an increase in “methogenic” bacteria, which has been associated with obesity.

SSRI antidepressants (Prozac, Paxel, Celexa and several others), particularly when used in people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), were associated with significant changes in the potentially harmful bacteria, Eubacterium ramulus. These drugs generally take a few weeks to exert their therapeutic effect; they also note that similar bacterial species are affected by different antiphychotics. This led to the suggestion that part of how both these types of drugs work could be by encouraging or blocking certain gut bacteria. Researchers hope that one day it may be possible to diagnose some brain conditions by analysing gut bacteria and to treat them with “psychobiotics” – specific mood-altering bacteria!

The German researchers also noticed that some drugs affect gut bacteria in a manner similar to antibiotics and these tend to have antibiotic-like side effects, such as digestive upset. They suggest that these non-antibiotics could be increasing bacterial resistance to antibiotics, since they affect gut bacteria similarly.

So, although this research is fascinating (or, at least, I think it is!), much more work needs to be done in this area. However, it shows that we cannot ignore the effects of various drugs on gut bacteria. Researchers estimate that one-quarter of drugs or more have an impact on the gut microbiome.

References:

Is your gut microbiome the key to health and happiness? – The Guardian

Many Common Meds Could Alter Your Microbiome – WebMD

Half of all commonly used drugs profoundly affecting the gut microbiome warn experts – EurekAlert

Many commonly used drugs may impact microbiome – Univadis Medical News